Vera Viselli

Pier Paolo Pasolini was a performer. Rather, he was a performative artist. This is the meaning of the exhibition OFFICINA PASOLINI

organized to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Italian writer, poet, director and intellectual loss.

After the huge exhibition in Rome, Pasolini Roma, which analyzed the dramatic and deep connection between Pasolini and the Capital city, with its borgate and its beaches, the exhibition in Bologna goes back to the poet’s roots, starting from the city where he grew up and had his educational path and where he came back in 1955 to create Officina, together with Roversi and Longhi.

The will is to embrace the whole Pasolini artistic production, with words and images, in a balance, giving the same amount of space to every artistic sector he worked on, creating a solid magma.

His completeness was remembered by Moravia at his funeral, during the function: «First, we have lost a poet. There aren’t a lot of poets in the world, just three or four born in a century. […] Then we have lost a novel writer. The writer of the borgate, of the street guys, of the violent life. […] Then we have lost the director that everyone knows, isn’t it? Pasolini has been the lesson of the best European cinema. He also made a series of movies inspired by that kind of his own Realism that I call Romanic, an archaic Realism, a gentle Realism, mysterious at the same time. Other movies are inspired by the myths, Oedipus’ myth, for instance. And then also film inspired by his great myth, the myth of the underprivileged classes, the classes owner of a kind of humility that could bring the world back to its palingenesis. He also presented this myth in Arabian Nights, for instance. There, it’s clear how the underprivileged class idea and the poor’s humility is extended by Pasolini toward the Third World and its culture. At last, we have lost a writer of essays. Although he was a writer with some Decadent fervor, although he was refined and manneristic, nevertheless he cared about the social issues of his Country, about the development of this Country».

OFFICINA Pasolini approaches Pasolinian artistic path through 9 areas.

THE EDUCATION YEARS. STUDIES WITH ROBERTO LONGHI

The educational period in Bologna with Roberto Longhi opens the exhibition. Together with various original documents about Pasolini’s educational path, we can see the drawings made by a young Pasolini of that Master who «showed us the images and it seemed we were watching a film». Also, it’s possible to watch an unreleased video from Bernardo Bertolucci’s private collection, Dino Pedriali’s photographies of Pasolini while he was working on Longhi’s portraits and the manuscript of Che cos’è un maestro.

MYTHS

This is the exhibition’s high point: the central hall is transformed in a Romanic cathedral’s nave, where multimedia installations stand for glass windows showing the myths which characterized Pasolini’s work.

The mother: Susanna Colussi, poetic and cinematographic inspirational source. Often described as a mother-child, her bond with his son was so strong to build up with him one only identity.

Friuli region: Bologna (the city of his father) represents the bourgeoisie culture; Friuli (where his mother was born) is the place of poetry.

Christ: in his Cinema, Pasolini uses the figure of Christ as role model for his suburb’s characters, from the Rome borgata. Accattone, Ettore Garofalo of Mamma Roma and Giovanni Stracci of La ricotta are, literally, Christs from the borgata, and so they die, acting through Christological gestures.

The classic tragedy: Pasolini has always been intersted in classical tragic theatre and in Greek mythology. Edipo all’alba is an outline for a pièce which revisits the story of Oedipus through the incestuous love of Ismene for his brother Eteocle. After Vittorio Gassman request, in 1960, Pasolini translated Eskilos’ Orestiade, for the theatre adaptation in Siracusa. There is also Medea (1969): Pasolini highlights the female magician archaic world that opposes to Theseus’ technological world. Also in 1969 he wrotes Appunti per un’Orestiade africana: an allegory of the transformation from an archaic world with no rules into the modern world of the Rational Rule.

The borgata: Pasolini moved to Rome with his mother in 1950; after the humiliation suffered in Casarsa, the suburban zones of Rome – the so called borgate – with their language, represented a real new world for Pasolini, not by choice but for «a sort of fate coaction». The Roman dialect spoken by the inhabitants of those shacks (surviving in archaic if not primitive conditions), with its cynical and joyous humor, absorbed Pasolini so much to become the main theme of short stories and poems, especially in the novels The Ragazzi and A Violent Life.

Lost populations: the Third World was – for Pasolini – the utopic idea of an untouched popular culture in opposition to the Western middle-class bourgeoisie. It’s also the dimension where he set his adaptation of Arabian Nights‘ tales, imagining a sexuality and a carnality released from every religious oppression.

ICONS

The section Pasolini and his time is about the transfiguration of icons (from the Marilyn in La Rabbia to Totò in The Hawks and the Sparrows) and the fight against the homogenization of culture. These characters acquires a new value through Pasolini’s perspective: Monroe is the image of an ancient and genuine beauty, that becomes inauthentic because of the capitalistic society; Maria Callas, acting as Medea, is no more a theatre diva but a woman humiliated and deprived of her mythical voice; Totò is a good philosopher, a tender and smart father and an inventive underprivileged who survived the changing of the world around him, where he keeps moving (comically) with slyness and melancholy.

CRITICS TO MODERNITY

In the middle of 60’s Pasolini already asserted the advent of a New Prehistory; but it’s from 1973 that his critic toward modernity comes in full shape through the articles published on the Corriere della Sera (all presented in the exhibition).

«The farming and preindustrial Italy doesn’t exist anymore and it’s been replaced by a vacuum which waits to be probably filled by a complete embourgeoisement», he writes in “Gli italiani non sono più quelli”, in June 10th 1974. The middle-class features, produced by hedonism and homogenization became the only and main identity in the 70’s Italy; Pasolini defines this phenomenon as a “catastrophe without precedents” and analyzes it continuously trying to investigate every anthropological aspect.

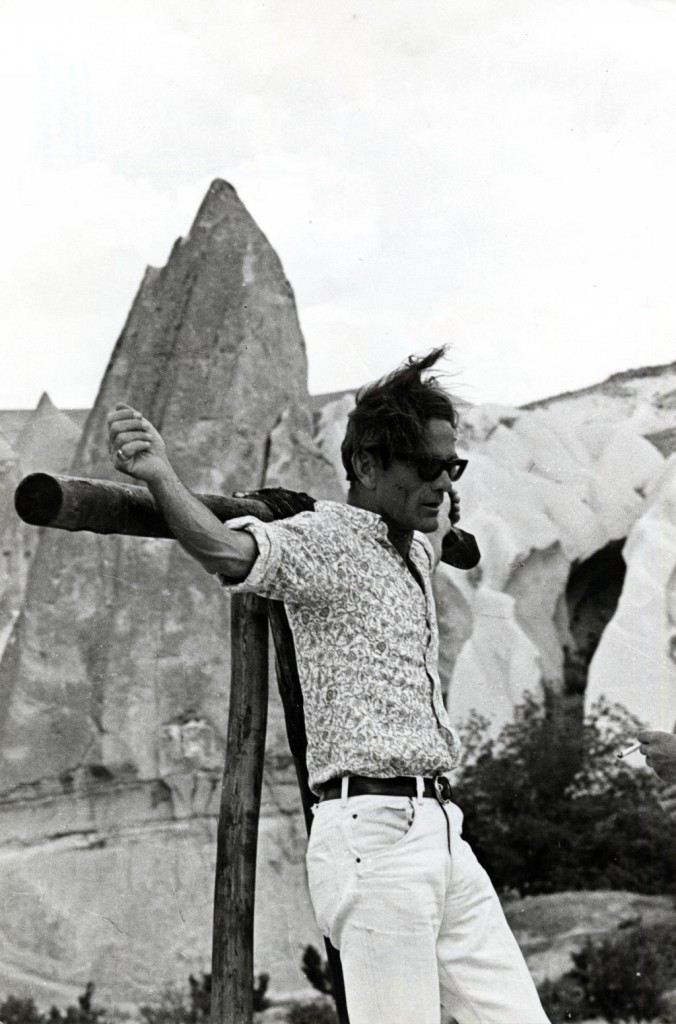

PETROLIO LABORATORY

Pasolini’s artistic testament is written – as he said – in Petrolio, a work left unreleased for 20 years and published only in 1992. The original project was to realize an unfinished novel (and it perfectly happened, since the premature death of its author). In October 1975 Pasolini chose the photographer Dino Pedriali to realize a series of pictures (also exhibited) which portrayed Pasolini in Rome, Chia and Sabaudia; these portraits probably should have been part of Petrolio iconography and are so full of beauty and intensity to become the poet image-symbols.

THE CIRCLE OF VISIONS

This circle includes the Decameron, the Canterbury Tales and the Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom and Petrolio’s Inferno. In his last years, Pasolini uses the Inferno image as a dimension of hallucinations which refers to real horrors; the dreamlike dimension is the deep key to obscure dynamics. As he wrote in Pigsty: «who ever knows what is the truth of dreams beyond the fact dreams make us impatient for the truth».

THE CIRCLE OF BOURGEOISIE

The main theme of the whole Pasolinian work is the bourgeoisie, with its presence and its absence, to be seen not just as a sociologic category but as a larger matter. In Pasolini perspective, bourgeoisie is the class which dictates its values and behaviors through an irreversible way since the 50’s. He firstly shows it through Theorem (film about the family unit which destroys itself as soon as an anomalous element is embedded) and then through Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom, the movie where the middle-class power (represented by the four Signori scellerati – the Duke, the Bishop, the Magistrate and the President) becomes pure anarchy, manipulating and destroying, respecting no rules.

THE CIRCLE OF TELEVISION

«In television, everything is realized in a flat, superficial, naturalistic way, with no care for the form. The long time spent with television made the innocent and normal audience to lose the meaning of the form, of the technically flawless work. […] My violent reaction is against the official culture: the culture, we could say, of television. Against the mass-culture which attacks us every day and it’s more and more unreal. Television is unreality. Everything which passes through the video doesn’t have relations with our life experience anymore» (Venice, September 1973).

The first Pasolini’s experience with television is in 1966, when he was forced at home because of an ulcer and, after watching several tv shows, he figured out some ideas, among them the lack of reality in television representation and the result of politics’ faces as simple masks.

PASOLINI AFTER PASOLINI

The exhibition path ends with the end of Pasolini’s life, with his death. There are the TV newscasts from 2nd November 1975, together with the artworks made by various artists who collected Pasolini heritage during the 40 years passed since his loss (for instance, Schifano’s portrait of Pasolini or the drawing made by the director Kiarostami).

Not among the exhibited documents but essential is the letter written by Oriana Fallaci on the 16th November 1975:

«You insulted in your writing, you hurt till you broke the heart. And I do not insult you saying that it wasn’t that seventeen years old guy to kill you: you killed yourself by him. I do not hurt you saying that I’ve always known you invoked death as others invoke God, that you longed your murder as others long to heaven. You had that need of absolute, you that obsessed us with the word humankind. Just ending with your head broken and the tormented body, you could stop your angst and satisfy your thirst for freedom. […] You left New York with disappointment because you didn’t die there, because you brought yourself to the abyss but you didn’t fall in it. The nights spent looking for suicide just left you with sunken cheeks, with feverish eyes. I feel, you said, like a child who’s been given a cake and someone stole it while he was going to give the first bite. Yes, you had to drink a thousand more of disappointments before someone gave you the gift of killing you, the gift of a coherent death for a coherent life. […] There was none else in Italy able to reveal the truth as you did, able to make us think as you made us think, to educate for a civil consciousness as you educated us. […] On tv screen, Giuseppe Vannucchi appeared and gave the official news. Also appeared the two humble persons who discovered your body. They said you didn’t even look like a body, from far, for so much you were battered. You looked like a junk pile and only after a closer look they figured out you were not garbage, you were a man. Will you mistreat me again if I say you weren’t a man, you were a light, and a light’s turned off?».

OFFICINA Pasolini

18th Dicember 2015 – 28th March 2016

MAMbo – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna

Exhibition promoted and realized by Cineteca di Bologna with the collaboration of Istituzione Bologna Musei | MAMbo

Curated by: Marco Antonio Bazzocchi, Roberto Chiesi, Gian Luca Farinelli with the collaboration of Antonio Bigini, Rosaria Gioiaprogetto.

Lightning by Luca Bigazzi

Info: www.cinetecadibologna.it – www.mambo-bologna.org

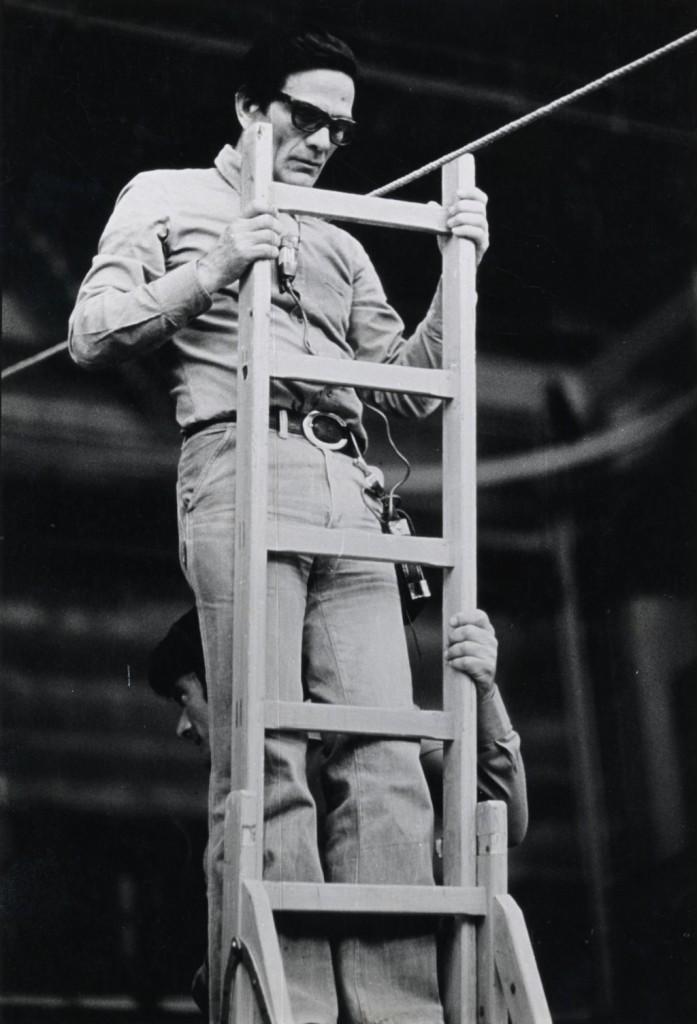

Cover: Pier Paolo Pasolini on set La ricotta, episode “Ro.Go.Pa.G”, 1963. © Paul Ronald. private Collection.