Giulia Pergola

During Postmodernism, Modern era positive values have been replaced by a critical consciousness which destroyed the “modern project (of universality)”[1] to reach a systematic deconstruction of the whole amount of previous period certainties.

Now, the work of art feeds itself with a more structured and diversified reality and gives back a self interpretation that is not univocal and, especially, is not based on a unique level of experience (the visual one). It requires a mix of elements (visual, verbal, conceptual) that have to be considered as one to get a fulfilled experience.

On the art critical side, Clement Greenberg chooses the formalist approach with a linear historical development.[2] Leo Steinberg identifies a breaking point in Robert Rauschenberg’s work.[3]

In Greenberg’s theory, modern painting is inclined to a deeper and deeper “purity” and so to a self-definition; it’s an attitude which takes place in the coincidence of the painted surface and the material support. According to this theory, since Impressionism bidimensionality prevailed on the illusionistic kind of representation. The physical matter of the painting support imposes its presence and automatically gives importance to the painting itself.

On the other side, the tridimensional space painted in the previous ages had the only purpose of creating a continuity among the real space and the pictorial space, as art dissembled itself.[4] Actually, the illusionistic game and the artist’s awareness of his/her technique skills determined an intense self-consciousness also in the art from the Past.

When Jan van Eyck chose not to use metals in his paintings and to reproduce the metal effect using only the brush, we face a kind of painting completely aware of its capability and by virtue of which can affirm its autonomy.[5] So the medium doesn’t censor art; art can reach its greatness thanks to its medium.

According to Steinberg, modern flatness of painting is at the base of the radical changing of art content. Steinberg uses the word flatbed (borrowing the term from the flatbed printing press) to describe, both in a material and conceptual way, the new kind of support used by some artists since 70’s. Searching no more for the reproduction of an illusionistic space, the flatbed is an opaque surface, a sort of board where images, information and data are stocked and recorded. Flatbed clearly recalls the relationship between things, by nature it deconstructs the phenomenological reality to let the structure emerge, moving the representation line from the vertical axis to the horizontal axis, from nature to culture.

In the artist’s studio, the easel disappears and the ground becomes the space of creation. The first series of Jackson Pollock’s drippings (1947) is the perfect example of this new kind of art production. In Full Fathom Five is possible to spot painting incrustations, coins, nails, cigarettes, and other non-pictorial material settled on the work’s surface, impressed and recorded on it. Fifteen years later, Andy Warhol read those stratifications and those heterogeneous inserts in Pollock’s works with a scatological meaning. In the Oxidations series (1972) Warhol’s friends have been invited to urinate on metallic painting covered canvas, giving back the same effect of the Action Painting through the oxidation of the surface activated by the uric acid. In this way, the uprightness and the fallic dimension of Pollock’s thought have been broken down, transformed in something low, dirty and ridiculous.[6]

In the early 50’s Rauschenberg makes a break with tradition, going out of the linear development of Greenberg’s theory[7]: his canvas becomes surface of work where photographs and non-artistic objects are collected, assembled and then leveled out by painting. His White Paintings are empty fields where lights and shadows are projected as it happens in photography but without any camera. Also the artist John Cage, Rauschenberg’s friend, was fascinated by those works and defined them as “virgin photographic surfaces waiting to receive an image”.[8] In 1949, a young Rauschenberg is introduced to the cyanography technique[9] by his future wife Susan Weil; the same year he realized a work (lost) made of the footprints of his college mates coming through the main door of the Art Students League of New York. White Paintings, cyanography, the stepped canvas are linked to the index concept defined by Charles Sanders Peirce at the beginning of 20th century, the sign that owns a straight connection with its referent. Dust cumulated on the white canvas recalls Man Ray’s photography of Marcel Duchamp’s La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (Le Grand Verre), titled exactly Elévage de Poussière. Actually dust is “one of the registrations of time. […] in semiology, it’s an index, like photography, but linked to the duration.“[10] Photography by the straight link with reality becomes a trace (index) of the world we live in. So there is a transition from a kind of art based on symbols and icons to a kind of art essentially based on the physical presence and on the trace.[11]

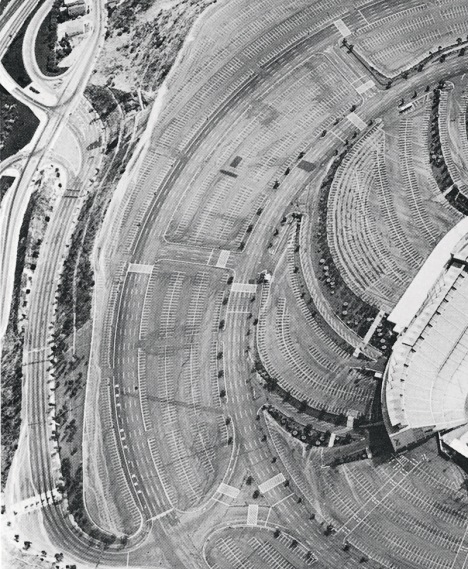

Meaningful is the example of Ed Ruscha’s series Thirtyfour parking lots (1967) in which the artist photographed thirtyfour empty parking zones from a helicopter. The aerial view gives the chance to capture oil stains left by the cars during the park. They are the index, the traces of human presence and the sign of time going by, but they are also the dirt, the formless, the entropy. So the parking series point out a double indexical process because both the photo and the real subject are index and it also talks about the concepts of formless and entropy often criticized in Postmodern artworks: Greenberg would probably associate all these characteristics to a “lowering of quality”[12] of art but actually they are both the cause and the effect of a changing society that is approaching to new experiences and languages more conceptual and structured.

* Quotes in footnotes are translated by the interpreter from an Italian version to English.

[1] G. Chiurazzi, Jean-François Lyotard. Postmoderno come delegittimazione dei metaracconti (1986), in Il postmoderno, Milano, Mondadori, 2007, p. 130.[2] C. Greenberg, Le ragioni dell’arte astratta, in Clement Greenberg: L’avventura del modernismo. Antologia critica, Milano, Johan & Levi, 2011. Talking about the anti-naturalistic attitude of abstract art, Greenberg defines a developing line that starts from Impressionism and reaches artworks of the latest 50’s.

[3] L. Steinberg, Neodada e pop: il paradigma del “pianale”, in G. Di Giacomo, C. Zambianchi (a cura di), Alle origini dell’opera d’arte contemporanea, Roma, Laterza, 2008. Unlike Greenberg, Steinberg doesn’t think about history of art as a continuum where each artistic view is the consequence of the previous one. Rauschenberg’s painting is a break point opposed to abstract expressionism and the other coeval compositive styles; now the main point is the image’s psychical references and its new kind of connection with the audience.

[4] In the essay Astratto e figurativo, Greenberg describes the main purpose of naturalistic paintings: “From Giotto to Coubert, the first assignment of the painter was to shape the illusion of a tridimensional space. This illusion were concieved as a stage.

[5] L. Steinberg, ibidem, p. 122

[6] R. Krauss, Y.-A. Bois, Orizzontalità, in L’informe. Istruzioni per l’uso, Milano, Mondadori, 2008, pp. 96 – 98

[7] C. Greenberg, ibidem.

[8] N. Cullinan, Robert Rauschenberg. Fotografie 1949 – 1962, Milano, Johan & Levi, 2011, p. 8

[9] C. Cheroux, La serendipity in fotografia, in L’errore fotografico. Una breve storia, Torino, Einaudi, 2013, p. 92. This kind of photography made putting an object at direct contact with the photographic paper was first experimented by William Henry Fox Talbot in the middle of 19th century and than in Man Ray’s rayographs. As he said “I used another kind of accident to create my rayogrammes. One day, while I was priting some photographies, an object randomly ended on the paper leaving a sign. After it I started to put keys, necklaces, pencils on the paper, letting the light impresses them. […] I found a process of making photographies without any camera.”

[10] N. Cullinan, ibidem

[11] ibidem

[12] C. Greenberg, ibidem, p. 390

In copertina: Ed Ruscha, Dodgers Stadium – 1000 Elysian Park Ave, 1967, detail, in Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles (1967), silver prints, cm 9.4 x 39.4. © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.